Robert Bruno, Ph.D.

Book Review

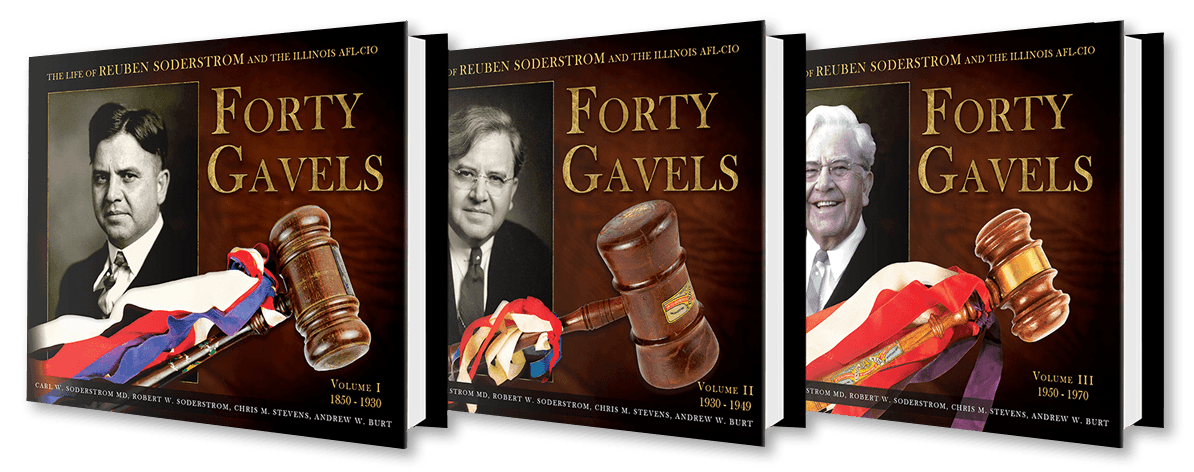

For me, contemplating the life of Reuben G. Soderstrom is like reaffirming a set of sacred vows that have existed since someone realized that one person’s labor could be a source of profit for another. His accomplishments are profound and working people in Illinois owe much to the labor-relations foundation that Reuben helped to build.

His life’s work is a testament to the contributions that labor unions have made in the development of a democratic state and nation. Against great odds organized labor created the core elements that lifted the material conditions of the masses. Clarence Darrow said it best: “With all their faults, trade unions have done more for humanity than any other organization of men that ever existed. They have done more for decency, for honesty, for education, for the betterment of the race, for the developing of character in men, than any other association of men.” And yet, as I engaged with the events of Reuben’s illustrious and extraordinary life I was constantly reminded of the irrational and often near manic opposition to unions that characterizes American history.

For example, in the1920s the Chicago Federation of Labor described Illinois Assembly representative Reuben G. Soderstrom as “capable and courageous” for fighting for legislation that protected workers and union organizing rights. His efforts won him the enmity of the Illinois Manufactures’ Association, which set out to defeat his re-election in 1926. They failed. Reuben went on to serve sixteen years in the state assembly and another four decades as Illinois’ highest-ranking labor official. In those years Illinois and America prospered. But despite Reuben’s and labors positive contributions to the country, the vitriolic campaigns against unions never ceased. Today a network of right-wing corporate funded anti-worker groups in Illinois and other states are actively soliciting union members to quit their labor organizations. Union and non-union workers should first consider the record.

During Reuben’s leadership tenure, labor in Illinois and across the country transformed America. One of the movements’ and Reuben’s biggest achievements was the adoption of state worker compensation systems to provide a strong safety net against the life-threatening and daily depilatory aspects of work. The idea of a “fair days wage for a fair days work” inspired millions to action and produced work hour restrictions and minimum guarantees against pauper-level earnings. Health and safety statutes were passed so that workers would not risk life and limb as they produced the nation’s wealth. Laws to prohibit child labor, defend organizing rights, recognize unions, prohibit forced labor and collectively bargain labor contracts were also among Reuben’s and the trade unions’ many proudest accomplishments.

Reuben was part of a movement that made it possible for working-class families like mine to buy houses and cars, afford medicine, save for a retirement, take a vacation, send their kids to college, afford holiday gifts, occasionally eat a better cut of meat and purchase a new winter coat. The social progress that Reuben and a generation of labor leaders and workers made possible is breathtaking and undeniable. An American middle class is unimaginable without organized labor. You would think that something so well done and beneficial would be settled practice. But instead Reuben’s shared legacy is at risk—not just in Illinois but almost everywhere.

Nearly half a century after Reuben’s death, state after state have attempted to roll back worker benefits, collective bargaining rights, and basic worker heath protections. As 2017 began there were seven more anti-labor Right-to-Work states than when Reuben gaveled his last state convention into adjournment. Reuben understood the hardscrabble world of labor relations and politics but I’m confident he would have viewed this new political reality as a form of insanity.

He was a visionary man who pursued big things. His world included U.S. presidents, civil rights leaders, corporate heads, military chiefs, university presidents (he is the “founding father” of the university school I teach in) and union leaders from Streator, Illinois to Washington, D.C. Reuben was not only an Illinois labor leader; he exemplified the characteristics of what political scientist once called a “national statesman.”

Statesman like Reuben could in 1956 lead the Illinois AFL-CIO to endorse Democrat Adlai Stevenson for president, while also supporting William G. Stratton, a Republican, for governor. When asked why the federation split their endorsement Soderstrom explained to the New York Times that it was because the incumbent Stratton had kept his word that there would be no anti-labor legislation in his administration. Hard now to imagine a time when America prospered on the strong back of a large, institutionally recognized labor movement.

In 1943 Rueben pledged the Illinois labor movements’ continued defense against fascism abroad. But he also made a promise that rings as relevant today as it did more than three-quarters of a century ago; to stand ready to defend against those at home who are “waging war on the wage earners of America.” Crazy and dangerous that what Reuben dedicated his life work to building is now once again up for grabs. But if it was once worth fighting for, it remains so today. If you need a reason to read the story of the son of an immigrant family who at age nine worked in a blacksmith shop and later as a printer and bottle blower before becoming a national leader for America’s working class, I couldn’t think of a better one.

Robert A. Bruno

Professor of Labor and Employment Relations

Director of the Labor Education Program School of Labor and Employment Relations

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

2018